Five people sat around a tray of cinnamon rolls in a small real estate office in the ranching and big game hunting town of Augusta, Montana. Mike Mueller, RMEF’s senior lands program manager for Montana, wrote $2,460,000 on a napkin, folded it over so nobody else could see and slid it across to lifelong rancher Dan Barrett.

When he opened it, Barrett cracked a small smile and said, “That’s what I thought you’d offer. Where’s all this money going to come from?”

Mueller said, “Well hell, Dan, I don’t know. But trust us. We’ll get it.”

“You know, against my better judgment, I do trust you,” Barrett replied. “But let me think on it.”

They shook hands all around and parted ways. This was the culmination of years of effort and there was a lot riding on the deal. The price on the napkin represented 442 acres of land so special, no amount of money could truly quantify the value to the public—especially those who love to hunt elk.

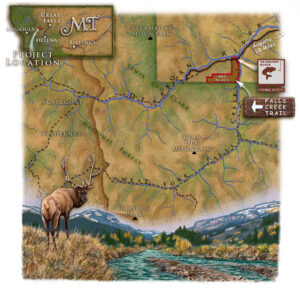

Toward the southern end of Montana’s Rocky Mountain Front, a thousand miles of prairie crash up against 800-foot limestone slabs, an ancient seabed thrust into the sky by massive forces. A small river splits those walls. It stills in pools so deep the sun slants down through ever-darker greens and blues but the bottom remains the province of imagination. Then it plunges down canyon once more. Arising from snowmelt and springs that tumble in a hundred rivulets from the high, wild reaches of the Scapegoat Wilderness, the Dearborn River definitely lives up to its name, though Lewis and Clark actually named it to honor Thomas Jefferson’s secretary of war.

“A HANDSOME, BOLD AND CLEAR STREAM”—So Captains Lewis and Clark proclaimed when they ascended from its mouth on July 18, 1805. Here the Dearborn River tumbles past new public land, a fine place to hop in and start fishing—or just hop in.

Five miles below where the Dearborn rolls out of the canyon, a major creek joins in, boosting the flow by half. Racing through gorges, swooping off ledges, pausing in aquamarine runs, Falls Creek is the distilled essence of the river it feeds—except for the 60-foot plunge that gives the creek its name. In its final run to the confluence, the creek flows due north. A faint trail runs beside it like a mile-long skeleton key through private land. Beyond that lies a feast of roadless backcountry on the hem of the quarter-million-acre Scapegoat Wilderness. Together with the adjoining Bob Marshall Wilderness, this is one of the last places in the Lower 48 where the entire original cast of predators and big game—from grizzlies and wolverines to mountain goats and bighorn sheep—still thrive. It was all there, a great sweep of outstanding public elk country only a mile from the road. If someone could just figure out how to unlock it.

Barrett held that key, as his father, grandfather and great-grandfather had before him. He owned those 442 acres of rich meadows framed by aspens, cottonwoods and conifers. The land cradled a mile and a quarter of Falls Creek, including the waterfall, plus a third of a mile of the Dearborn. And it backed up to national forest.

“I grew up on this land. All my best memories with my dad come from here,” Barrett says. “We were horseback. We were riding, you know. We spent an incredible amount of time up here working with our cattle. Riding long days. It was hard work, but we loved it, and we did it together.

“My own son Wyatt has done the same. He’s only 14 but he’s been riding up here with me for years, moving cattle. I’m not going to lie to you. The idea of selling it was bittersweet.”

“ALL MY BEST MEMORIES COME FROM HERE”—Wyatt and Dan Barrett working cattle up Falls Creek on land that belonged to their family since Dan’s great-grandfather homesteaded it when Montana was still a territory.

One of the other people around that table in the realtor’s office was Bryan Golie. He got his first taste of Falls Creek when he was a college kid in the summer of 1992, out riding with family on a pack trip that carried them on a big loop through the Scapegoat Wilderness.

“There are a lot of places in that country that take your breath away, but I remember reining up and seeing those falls for the first time and thinking that had to be one of the finest,” Golie says. “I never thought in a million years I’d be back here working to get it open for the public.”

The national forest ended a mile shy of where Falls Creek passed under the Dearborn Road and joined the river. Back then, use was relatively light and there was still sufficient goodwill to allow people to cross private ground on either side of the creek to reach public land. It didn’t last.

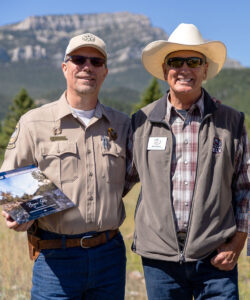

These days Golie works as a criminal investigator game warden for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks (FWP) along the Rocky Mountain Front, and a land access coordinator on special projects. He devotes two-thirds of his time to nailing poachers and the other third to creating more public access to high-quality hunting and fishing opportunities.

“There’s a tremendous amount of history tied to public access here on Falls Creek, bad and good,” Golie says.

The former is as ugly as it gets. Joseph Campbell owned the land on the upstream edge of a remote subdivision of three dozen houses and cabins near the mouth of Falls Creek. In a long-running dispute with his neighbor, Timothy Newman, Campbell claimed that he held exclusive control over access up the east side of the creek. The feud boiled over on October 18, 2013. Gunshots tore the air and Newman, 53, lay on the ground, gazing forever up Falls Creek to the mountains beyond.

There were no witnesses. The story held so many dark twists NBC’s Dateline devoted an entire episode to it in 2016 and HLN’s Vengeance: Killer Neighbors featured it again last year. Campbell claimed self-defense, but he’d had similar clashes with many of his neighbors and they lined up to testify against him. After a 14-day trial with more than 50 witnesses, though, the jury deadlocked and the judge declared a mistrial. Facing retrial on deliberate homicide charges, Campbell pleaded no contest to negligent homicide, got a 20-year suspended sentence and agreed to never again set foot within 10 miles of the subdivision on Falls Creek.

And the good? Well, public access victories don’t come much sweeter. The Barretts had been great stewards of their land along Falls Creek and the Dearborn for 140 years. If RMEF could acquire that land, it would become part of the Lewis and Clark National Forest and serve as a portal to outstanding habitat for elk, mule deer, wild trout and a wealth of other wildlife. Those grass-filled basins and fir-cloaked slopes lie 16 hard miles and many vertical feet by trail from the nearest public access point.

“This would have been an amazing project even if what we bought was a piece of dried out, pounded flat dirt—purely because of the gateway to the Scapegoat backcountry,” Mueller says. “Instead, it’s a paradise with not one but two trout streams and the most beautiful waterfall you can imagine.”

Golie and Mueller had teamed up for the better part of a decade to protect key habitat and open access, notching multiple wins on the Rocky Mountain Front. Along the way, they built an easygoing trust in one another.

It was two years after Campbell gunned down his neighbor when Golie first told Mueller, “If this place ever becomes available, we’ve got to jump on it. I don’t even know how it might happen, but I’m studying on it. I know we’ve got to go slow and

get it right.”

That’s exactly what they did. Golie specializes in catching habitual poachers—the people who kill trophy wildlife over and over again—using a behavioral profile he developed. He has trained himself to absorb and scrutinize details that appear minor and random until the underlying patterns begin to emerge. There is real satisfaction in cracking wildlife crimes, but it’s grim work. So the part of his job where he gets to create public access to great places is like a giant helping of huckleberry pie. Still, he brings the same patience and deceptively casual intensity to the task.

“I was acutely aware of the potential there on Falls Creek,” Golie says. He tried to learn everything he could about the area and the opportunity from longtime fellow warden Dave Holland and FWP’s wildlife biologist for the area, Brent Lonner.

Then he picked up the phone one day early in the fall of 2016. Barrett was willing to listen and Golie pitched him everything from a short-term access agreement to buying the land.

“Look, I’ll take it all into consideration. I’m not doing any kind of short-term agreement,” Barrett replied. “If you want to end up with the property, I would consider that. But not now. If you just give me your personal information, I’ll get ahold of you when I’m ready.”

The first rule of fishing is keep your bug in the water. That’s what Golie did, resisting the temptation to call. Green-up was in full swing the following spring when his phone rang. It was Barrett. He said, “Okay, now I’m ready.”

Fortunately, Mueller and Golie had recruited Jeanne Holmgren, real estate specialist with the U.S. Forest Service. They were ready, too.

“Jeanne is outstanding. We love working together. She’s been a huge force behind many of the greatest wins that RMEF has had in Montana over the past 20 years,” Mueller says. “As usual she jumped in with both feet.”

Senator Steve Daines (R-MT) delivered the keynote speech on the banks of the Dearborn. He and Sen. Jon Tester (D-MT) played a crucial role in securing key funding from the Land and Water Conservation Fund at a critical time to complete the acquisition. Thanks to their work, the public gained access to 27,000 acres of great elk country in time for opening day of Montana’s archery elk season.

Holmgren was there in Charles Taylor’s realty office that day, too, assuring Barrett that the Forest Service would care for the land with same dedication his family brought to it across four generations. That kind of teamwork—in this case between a state wildlife agency, a federal land management agency and RMEF—is the hallmark of what it takes to make a lasting difference on the landscape today.

“The Elk Foundation was built on partnerships,” Mueller says. “It’s still the most important thing we do and the greatest asset we have. We wouldn’t be anywhere without those relationships and those folks wanting to work with us.”

Blake Henning, who oversees all permanent land protection and habitat stewardship work as RMEF’s chief conservation officer, echoes that sentiment.

“Partnerships have been the heart of our approach and our success right from the start,” Henning says. “In these times when there’s so much divisiveness, we stand for bringing people together to achieve what none of us can do alone.”

Holmgren, Golie and Mueller were hopeful when they met Barrett for the first time at Taylor’s office. Still, they had all been involved in enough land deals to know how many ways there are to get it wrong and watch the dream implode.

“But Brian has so much heart and he was so sold on what this was going to mean for the common man and woman that you could literally see Dan start to feel the spirit,” Mueller says.

After listening a while, Barrett said, “Wow, this is pretty important. I’m always getting hunters coming up here asking, ‘Where can I find a place where I can walk in and hunt?’ Well, here’s one where you can walk in as far as your legs will carry you. And the animals are there.”

For his part, Barrett made an equally strong impression on the team.

“I could tell he was a man who knew what it meant to do rugged work in everything this country can dish out,” Mueller says. “It was clear to me that he valued his family’s heritage, valued his son and valued his land. He in no way acts like a king—he’s

as down to earth as they come—but he definitely sees his family’s land as a kingdom that he’s been entrusted with.”

At the end of the meeting, Barrett shook Golie’s hand and looked him in the eye.

“I knew right then, you shake his hand, it’s the same as a contract,” Golie says. “We maintained that attitude all the way through. We never promised anything we didn’t deliver.”

Good intentions notwithstanding, countless deals have broken apart on the rocks of appraisals deemed too low by the seller or too high by the buyer. The stakes are even steeper when the federal government is the ultimate buyer (in this case via the U.S. Forest Service), because it is prohibited by law from paying even a cent over a property’s appraised value. Luckily, the seller was a man who could close his eyes and envision every foot of the land in question, feel the way each swell and dip relayed up through the hooves of a good horse.

“I don’t do anything on a whim. If I was going to sell, I had three ways to go. I could make the most money by subdividing it and selling it in pieces. I could sell it outright to a private buyer. Or I could sell it to the RMEF knowing it was going to become national forest,” Barrett says. “No way in hell did I ever want to see this subdivided or degraded.”

After he pushed the napkin across the table to Barrett and shook his hand, Mueller headed south on Highway 287. He was barely 10 minutes out of town, rolling through a set of steep hills, when his phone rang. It was Barrett. Cell service is spotty and the shoulder is skinny through there, so the best Mueller could do was edge over half off the road at the top of a long hill and keep an eye on his rearview.

“IF THIS PLACE EVER BECOMES AVAILABLE…we’ve got to jump on it.” That’s what Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks game warden Bryan Golie (left) told RMEF’s Montana lands program manager, Mike Mueller (right) in 2015.

Ever to the point, Barrett said, “Mike, I’m going to do it.”

“Really, Dan? Don’t you want to think about it a little bit longer?”

“Nope. This is the right move for me and my family—and for the public. My word is my word.”

Meanwhile, Golie had pulled up behind Mueller in his FWP warden’s truck.

“Turn on your lights so we don’t get killed,” Mueller hollered back to him. “Then come here.”

After saying goodbye to Barrett, he jumped out of his truck and shouted, “We got it!” Golie gave a whoop. Then the two of them did a happy dance in the middle of the empty highway.

Afterwards, as he turned toward his truck, Golie said, “Okay, I got you the deal. Now you take it

from here.”

“Wait, where are you going, man? We’ve got two and a half million dollars to raise.”

Golie said over his shoulder, “You do that.”

RMEF’s standard protocol is to have all the funding in hand before we make an offer. In this case, though, our board of directors agreed that Falls Creek was a place of such exceptional value that the organization was willing to put its name on the line for the full purchase price.

Fortunately, RMEF has an abundance of great partners from fellow nonprofits to outdoor companies to private individuals, plus federal, state and—especially in this case—county governments. When an opportunity like this comes along, everyone digs deep to chip in. RMEF’s development team flew into action and before long, RMEF had $1 million in hand.

In 2010 the citizens of Lewis and Clark County voted to pass a $10 million open space bond, voluntarily raising their own taxes to keep key pieces of land intact and to create more public access to those places in the face of ever-expanding development.

“The voters funded that bond with the understanding that we, the leaders that they charged with that duty, would put together the strongest projects we could to preserve working ranches and farms, protect wildlife habitat and deliver public access,” says Andy Hunthausen, who’s served as a county commissioner since 2007.

Helena anchors the county’s southeast edge and many rural voters were skeptical that the bond money would ever reach beyond the donut of land ringing the city. As it turned out, the single largest chunk of that bond went to open a magnificent place 75 miles northwest of the state capitol.

Peter Italiano serves as director of the county’s open lands program. A longtime elk hunter, he immediately saw Falls Creek as a flagship project to drive home to everyone who voted on that bond nine years ago just how important their money is. He encouraged RMEF to apply for open space funding and we swung for the fence, asking for $1 million. The county commissioners showed real interest and put the proposal out for public comment. Meanwhile, Italiano urged Mueller and Golie to invite the commissioners to tour Falls Creek.

The day after the tour, Italiano called Mueller and said, “They’re so damn excited about this you should probably ask for more.”

When Mueller went back before the commissioners, Hunthausen asked, “How much do you need to get this across the finish line?”

Mueller replied, “If you give us $1.4 million, we’ll be celebrating it this summer and have it open in time for the first day of archery season.”

When the commissioners voted, the verdict was unanimous.

“Every project that we’ve completed with money from the open space bond, people have been split: total waste, vitally important,” Hunthausen says. “We received more feedback on Falls Creek than any other project and I don’t remember a single negative comment. I’m so grateful to the citizens of Lewis and Clark Country for having the wisdom to pass this bond, and so happy to use part of it for something of this magnitude.”

That gratitude runs both ways.

“My hat’s off to the Lewis and Clark County Open Lands program,” says RMEF’s Henning. “We’ve partnered with a number of counties on bonds like this over the years, but we’ve never seen this kind of enthusiasm or contribution. Incredible.”

Gary Sullivan retired after 30 years of working for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on the Rocky Mountain Front. Then he went right back to work for the nonprofit Conservation Fund.

“We are absolutely a partnership-driven organization and RMEF has long been one of our best,” Sullivan says. “We share the same philosophy about the challenge of creating access to great hunting and fishing, and protecting the most special places. Falls Creek is the epitome of both.”

As supervisor of the Lewis and Clark National Forest, Bill Avey is now charged with stewardship of the land that the Barretts cared for so well. Avey invokes the man who created the agency he’s spent his career working for.

“Theodore Roosevelt told us, ‘Far and away the best prize that life has to offer is the chance to work hard at work worth doing.’ So many people who made this project happen have devoted their lives to doing just that, with Dan and Wyatt Barrett at the top of the list,” Avey says. “It’s humbling to have a small part in carrying that work forward.”

ALL YOURS—The view up Falls Creek into roadless backcountry and the Scapegoat Wilderness beyond.

As for the Barretts, they have no intentions of getting out of the cow and grass business. Their home and ranch headquarters lie just a few miles north and east from the mouth of Falls Creek. They’re probably out working cattle right now.

Jay Erickson chairs the Montana Fish and Wildlife Conservation Trust, which made a significant contribution to the effort, as it has on many prior RMEF projects. Created by federal legislation in 2000, the trust exists specifically to replace lost habitat and especially lost access.

“It’s a great feeling to be part of the team that made this possible,” Erickson says. “It’s even greater to know this place is not going to be populated with trophy homes but grizzlies and trophy elk.”

As the dedication approached, Mueller asked Barrett if he had an old hay wagon that could serve as a stage. Quick to oblige, Barrett texted him a shot of what he had in mind.

“It was kind of a dinky wagon with a deep belly and a device on the back that spun. I said, ‘Yeah,

it looks a little small, but we can probably make

that work.’”

Barrett let him dangle a while then sent another text, “You know what that is?”

Mueller had to admit he didn’t. Barrett called him up and broke the news.

“It’s a manure spreader,” he cackled. ”I thought it fit you.”

GREAT PARTNERS—Jeanne Holmgren, real estate specialist for the U.S. Forest Service, RMEF’s Mueller and Chief Conservation Officer Blake Henning, and Lewis and Clark National Forest Supervisor Bill Avey (from left) celebrate a huge win for public access at the dedication August 27, 2019.

On the day of the ceremony, of course, Barrett delivered a full-size, old-fashioned hay wagon and parked it level in a meadow a stone’s throw from the Dearborn. Nearly a hundred people gathered to celebrate the newest piece of the Lewis and Clark National Forest on the morning of August 27. Charles Taylor, the realtor who brokered the deal, played the fiddle as people took their seats. Then the sound of water just down from the mountains provided the accompaniment as everyone from U.S. senators to the rancher who made it all possible stepped onto that wagon and spoke.

They marveled at the power of people pulling together to do something that will live on long after all of them are gone. Reveled in the joy of roaming free in wild country. Shared stories of this place, old and new. The pastor who delivered the blessing to open the ceremony told of his grandmother skinnydipping with Barrett’s grandmother just upstream from the meadow on another hot August day.

As for Golie, the man who first dreamed of seeing this become public land, he said, “Hunting is a huge part of my life and my heart really went into this because of what it does for hunters. I hope I’m here to see the first elk packed out and take that picture. I’ll send it to everybody and say, ‘Look, this is what you’ve done.’

“But yesterday I had a family stop by that simply wanted to walk to the falls. They just wanted to see it. They took pictures. They walked back. To them, that was priceless. How do you beat that?”

Everyone who spoke expressed gratefulness, most of all to Dan Barrett.

When his turn came he said, “Today really drove home to me this is not about Augusta or Lewis and Clark County. It’s not about Montana. There are going to be people from all over the nation coming here. Weddings are going to happen at the falls. Six-point bulls are going to come down that trail on the backs

of mules.”

He paused and looked up at the land where his family had worked and played since Montana was a territory. His eyes traveled on to Bear Den Mountain and the high stone ramparts beyond. Then he turned back to face the crowd.

“Two hundred years ago, this land belonged to everyone in America. It was held by the federal government until they offered it up for homesteading. It’s been in my family ever since,” he said. “Now it’s come full circle and belongs to the American people once again. I’m good with that.”