What do elk teeth and tree stumps have in common? Both can be aged by counting their rings.

Here’s how it works and why it matters.

by Tana Wilson

Editor’s Note: This is the second edition of a 3-part series about scientific aging using elk and other wildlife teeth— a service now offered to hunters through Matson’s Laboratory.

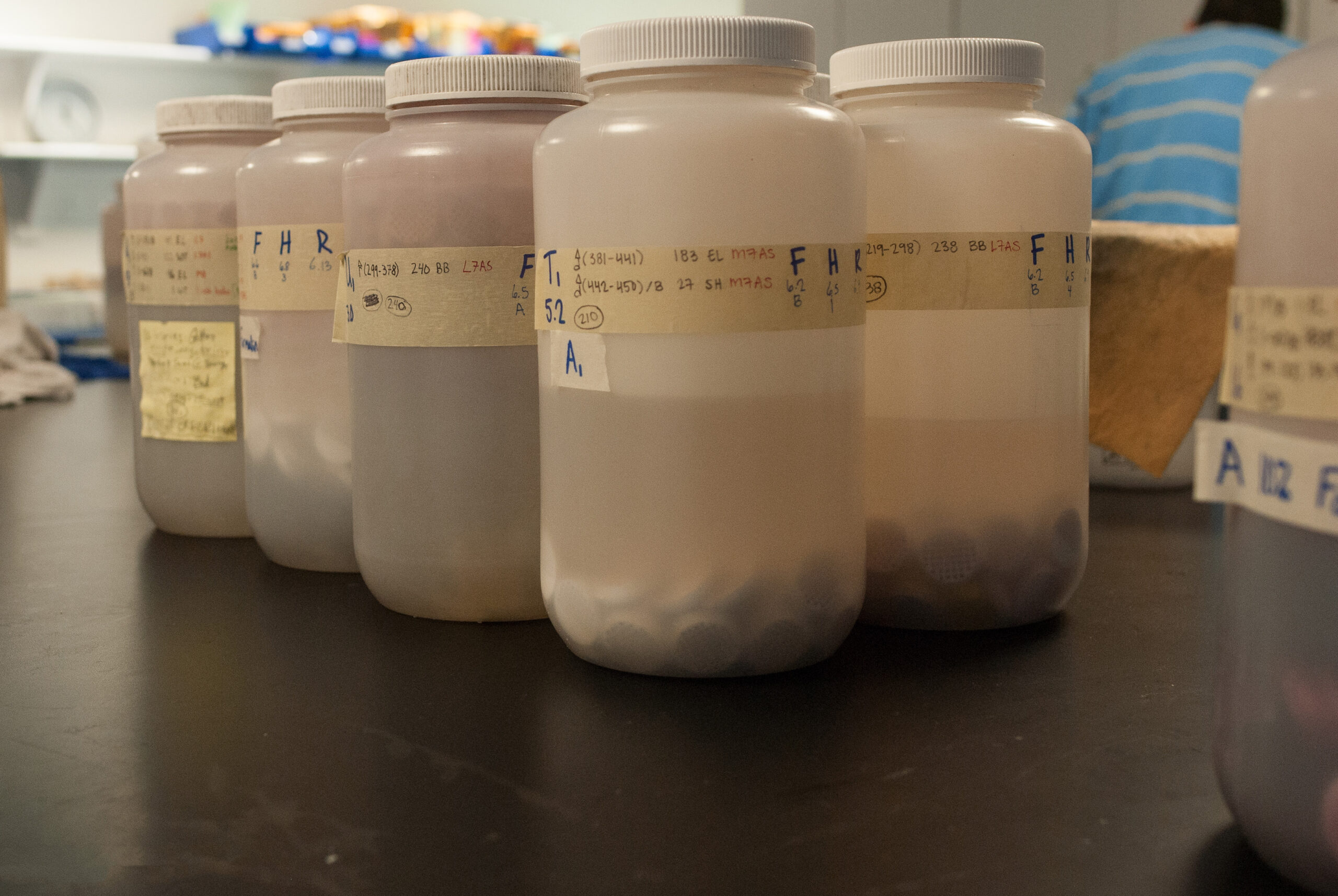

If you find yourself curious how old an animal is, there’s a good chance Matson’s Laboratory can tell you. It usually takes about two months to process and report back—not too much different than dropping a head or antlers off at a taxidermist.

The opportune time to extract a tooth is right after death. Once the tissue begins to stiffen, it’s far harder to free it from the gum. If a tooth breaks at the gum line, it is impossible to use cementum to age it. The best extraction method is to slice down on each side of the two lower front teeth with a sharp knife. Then wiggle one back and forth until it can be pulled free.

The oldest elk the lab has so far aged was an incredible 32 years of age, a cow elk from Pennsylvania.

In addition to more than 3,000 teeth from black bears, the Pennsylvania Game Commission ships one tooth from every elk legally killed in the state’s hunt—more than 100—plus some elk that die from other causes.

Tricks of the Trade

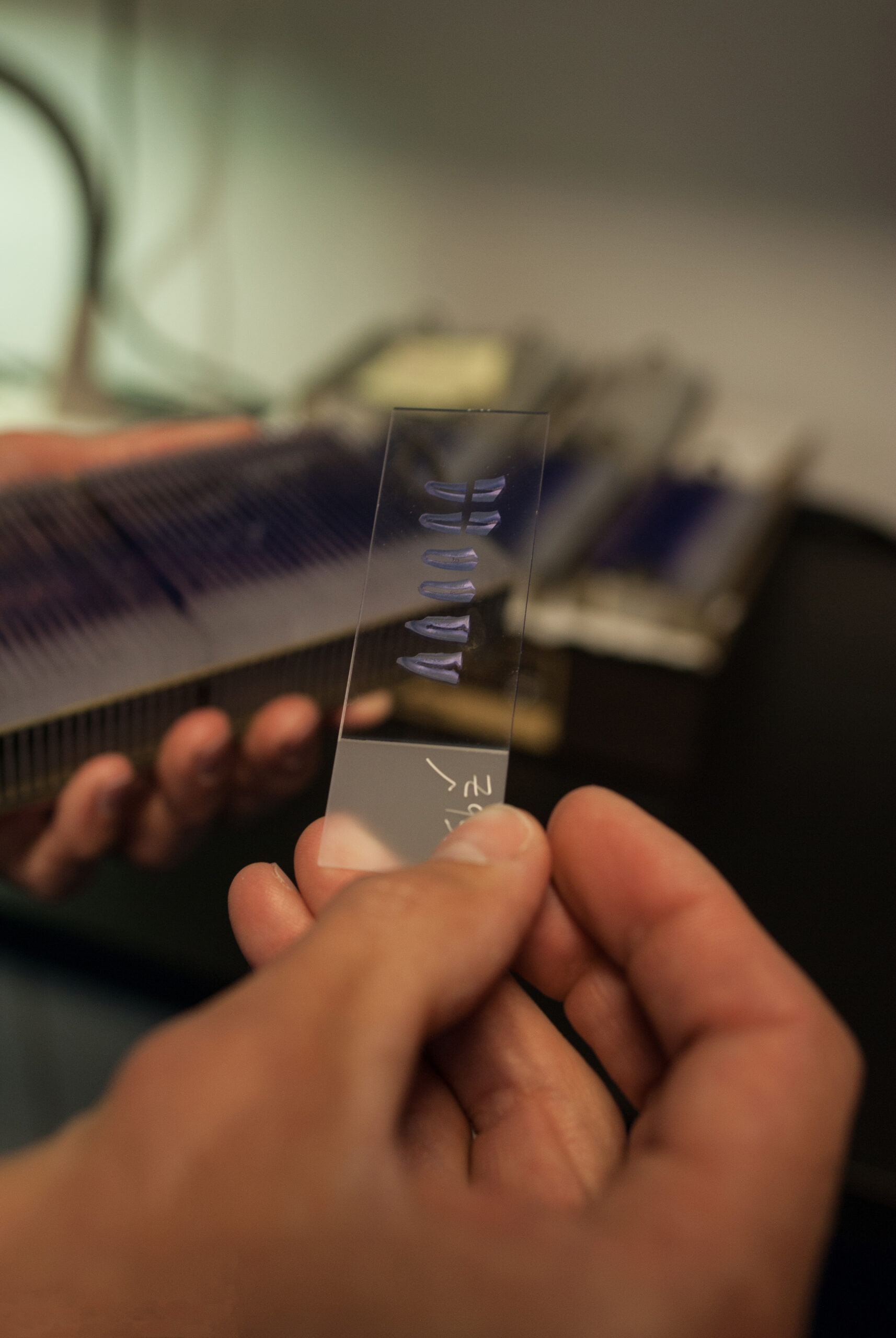

Matson’s cementum age analyses are species-specific and based on a standardized tooth type. Lab technicians must also account for the anatomical differences between species. For instance, bighorn sheep have four pairs of incisors that erupt in four consecutive years. If a technician aged the first-year incisor as though it were the incisor erupting the fourth year, the age count would be off three years, so it’s critical to identify the specific tooth type before counting cementum deposits.

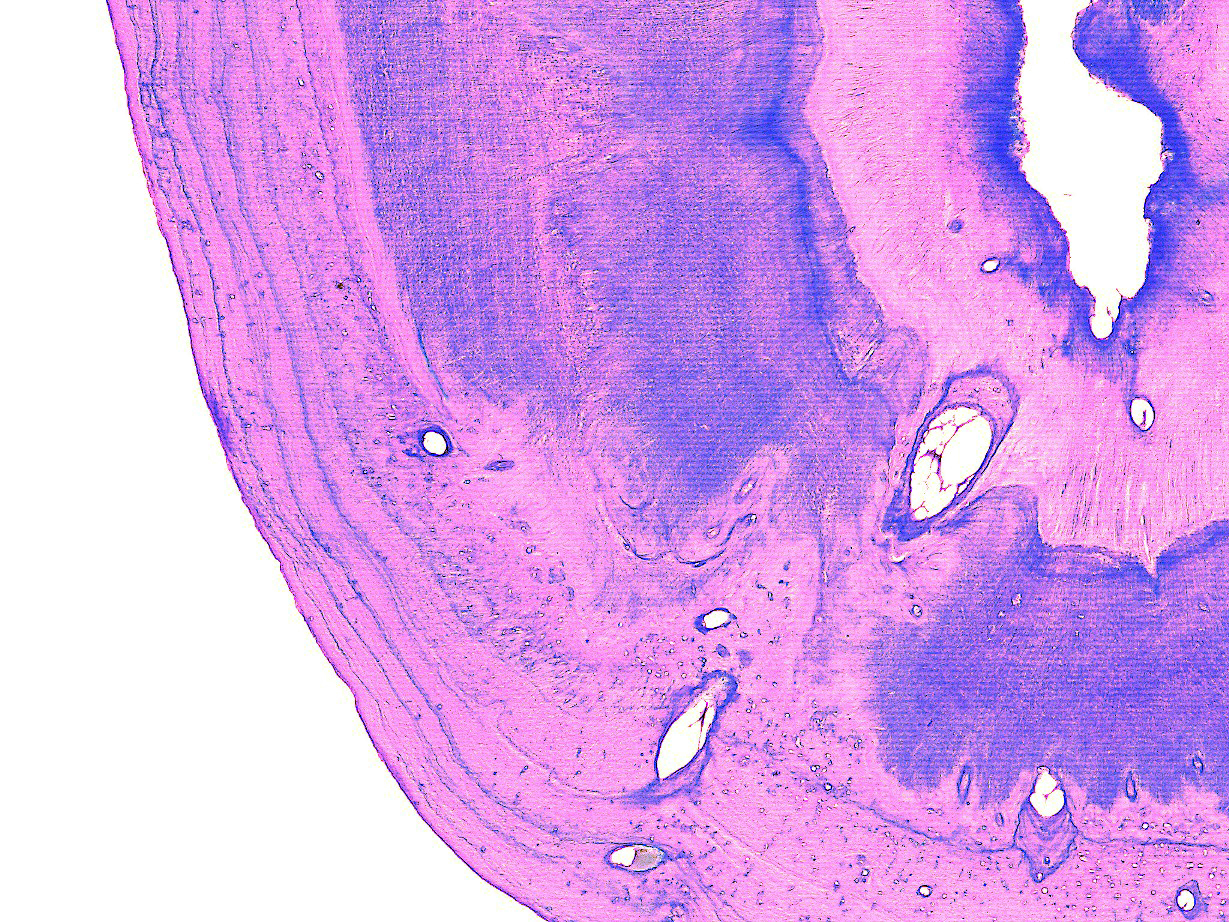

In the winter, when food tends to be scarce and low in nutrients for elk and other big game, they deposit dark, narrow growth bands. Then in spring and summer when resources are abundant, they deposit thick, light bands. The dark bands are what agers count to determine how old an animal is.

For the most part, animals that are five or older are easier to age than those that are younger.

Secrets told in Teeth

Some animals have very distinct layers of cementum that are like counting rings on a tree—but others are more difficult. Lab owner Carolyn Nistler says mountain lions, river and sea otters and polar bears are among the more challenging species to accurately age. Their protein layers look more like a meandering stream than a linear ring.

Cementum deposits are also a lot like rock layers—if you look closely, you can infer what might have occurred in the past. For example, while aging female black bears, Nistler and lab manager Arthur Stephens can often pinpoint exact ages when a sow reared cubs.

“Years where the lines get scrunched together are the years the sow had to rear the cubs and couldn’t get as much nutrients for herself,” Stephens says. “Once the cub is a year old, we see that sow is more self-sufficient, and the lines spread out more.”

Bizarrely, they don’t see that in any other bear species. Stephens has aged 1,300 polar bears— equivalent to roughly 5 percent of the current world population—and has never been able to differentiate between years with cubs and years without.

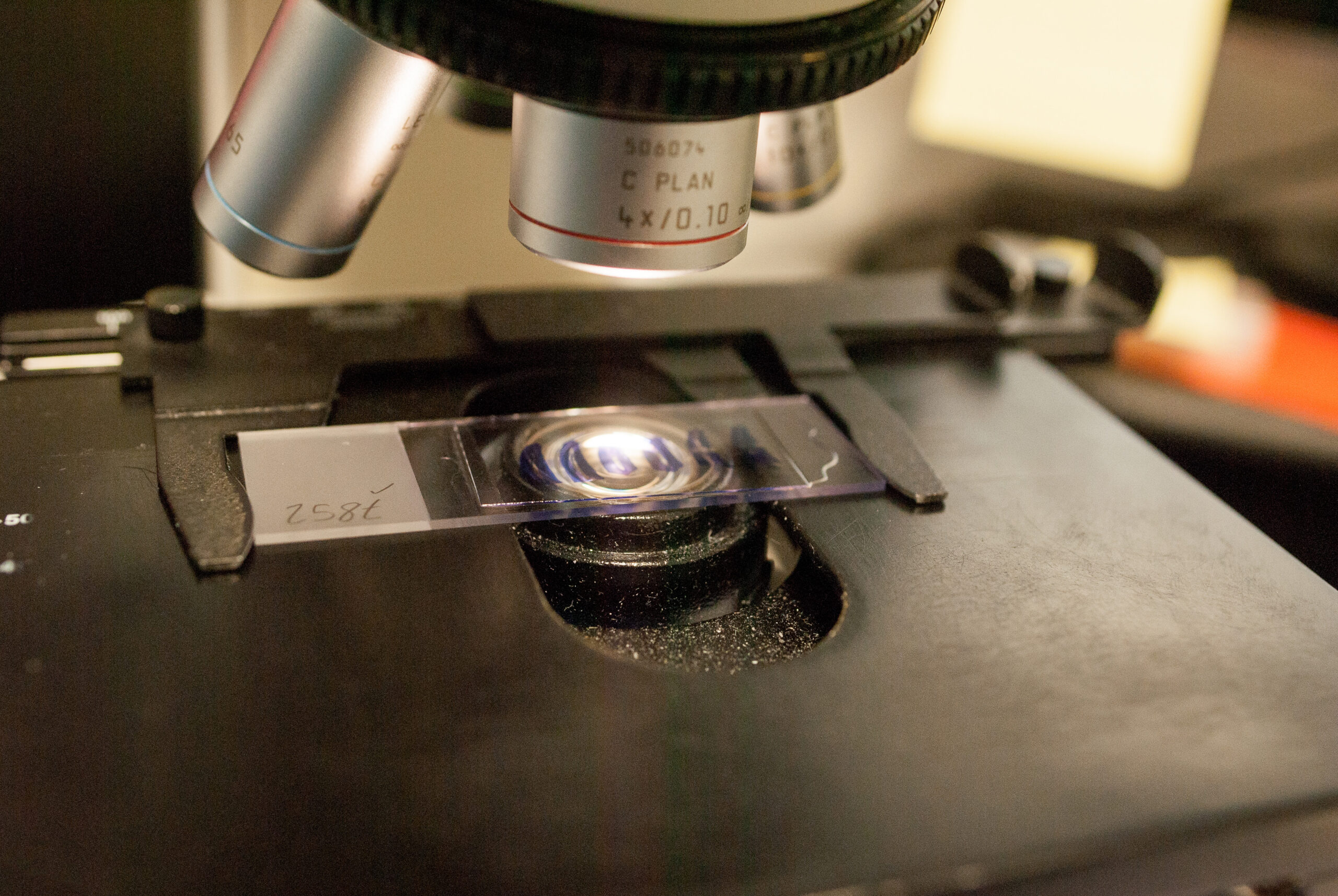

Microscope information:

A Species that Can’t be Aged

There are very few North American wildlife species that the lab hasn’t aged. Even species with continuously growing incisors such as beavers can be aged using their molars, and Matson’s Lab has processed quite a few.

For many years one critter they’d never aged was a snake. But that changed recently when the lab received a tooth from a reticulated python from New Caledonia, which they estimated to be 7-10 years old.

There is one thing that’s impossible to age, though, even though it doesn’t lack for teeth—in fact it has at least 300 of them. Shark species defeat all attempts at using cementum for aging because they continuously replace their teeth as they break off or wear down, never laying down any rings. In fact, sharks can go through 30,000 teeth in their lifetime.

But for the rest of the animal kingdom, no other cementum lab in the world has aged as many different critters or processed as many teeth as Matson’s Lab.

“We add a handful of new species each year,” Nistler says.

To learn more about cementum and how hunters can send in teeth from game to get them aged, visit www.matsonslab.com.