The herd spooked. Bulls, cows and yearlings ran full tilt across the field toward a range fence—one built for cattle and strung with five strands of barbed wire. The bulls poured across it like show horses over jumps, and most of the big cows, too, cleared the wires and kept running. But in the rush, elk began to bunch up against the barrier. Some hesitated before leaping, some balked and turned, looking for an easier way through. Pushed from behind, animals jumped in panic, scraping over the barbs, wires twanging like an untuned guitar. One cow crash-landed hard onto her chest. Another caught her hind leg in the top wires, struggled for a heart-stopping minute, and broke free, running on but limping hard.

This scene played out not far from the National Elk Refuge in Wyoming, but it could have occurred anywhere in elk country. When we see big, healthy elk, moose and deer sail effortlessly over a fence, it’s easy to assume they cause little problem for wildlife. But fright or inexperience, small size, depleted condition, injury, deep snow, steep slopes, rocky ground, loose wire or just simple miscalculation can make it tough for animals to navigate a fence safely.

We erect fences for myriad purposes, from the practical to the aesthetic. They are essential for livestock operations; they protect property and sensitive habitats, demarcate boundaries and keep animals off of highways for safety. In fact, they are such a common part of the landscape that fences often fly under our conservation radar—almost invisible when we’re thinking about wildlife habitat. Yet to elk and other wildlife, fences are a serious hazard and barrier.

It’s not uncommon for ranchers to have to cut the carcasses of elk, deer, antelope and moose out of their fences—legs fatally caught and twisted in the wires when the animal tried to jump. Trapped and struggling for hours, sometimes days, is a brutal way to die. Animal damage to fences also costs landowners dearly in time, labor, materials and heartache. There are invisible costs, too, for animals that frequently need to cross fences on the landscape: leg injuries, wounds and hair loss from barbs, loss of vital energy during lean winter months, being blocked from food and water or stalled on migrations. Wherever we can remove obsolete fences and build or modify fences with “wildlife-friendlier” designs, we can reduce maintenance costs, save lives and open up landscapes.

Thwarted, Torn, Tangled

For all the millions of miles of fence strung across the West, do they really cause that much harm to elk and other wildlife? While even one animal lost to a fence is a sad waste, it’s hard to quantify the full extent of the impact, but one study revealed some sobering numbers.

In 2006, Justin Harrington published his graduate research on ungulate fatalities in fences. Over two years, Harrington rode more than 600 miles of fenceline in northeastern Utah and northwestern Colorado. Big herds of elk, mule deer and pronghorn inhabit this region, where sagebrush, conifer and aspen cloak the mountains and ribbons of willow and cottonwood line the streams, all of it intermixed with farmlands and grazing lands. Over two years, Harrington recorded the number of elk, deer and pronghorn carcasses found in or near fences.

Harrington found that, on average, one ungulate per year was caught and fatally tangled for every 2.5 miles of fence. Most died after getting their legs caught in the top two fence wires. The most lethal type of fence was woven wire (also called sheep fence or field fence) topped with a strand of barbed wire. As you might expect, young animals were eight times more likely to die trying to jump a fence than adults, and mortalities peaked in August, the time when young are weaned and become more independent.

While a carcass caught in a fence is grisly and tough to miss, there’s a more invisible heartbreak. Harrington often found carcasses lying near fences as well—an average of one animal per 1.2 miles of fence each year, twice the number he’d found ensnared. Ninety percent of these were the remains of fawns and calves found lying in a curled position. Tragically, when these young ones could not follow their mothers under or over a fence, they simply curled up to wait and eventually died of exposure, starvation or predation. Most of these casualties were found next to woven wire fences.

Fences pose barriers to animals trying to access food, water and seasonal habitats. They can also delay and block migrations. A BLM-funded telemetry study of mule deer from 2011 to 2013 conducted as part of the Wyoming Migration Initiative discovered a previously unknown long-distance migration: these deer trek 150 miles between summer range in the Hoback Basin to winter range in the Red Desert. Each round trip, they have to navigate an average of 170 fences.

Opening Up the Range

The best situation for wildlife, of course, is no fences at all—free and open country without the hazards and barriers of fences. Wherever a dilapidated and unused fence can come out, it’s an opportunity to open things up for wildlife—and people. We all relish that wide-open, “Don’t Fence Me In” sense of freedom. You can almost feel the land breathe again.

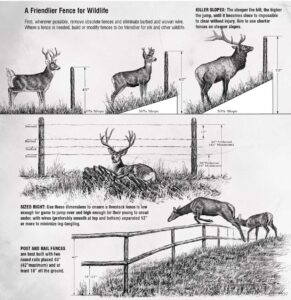

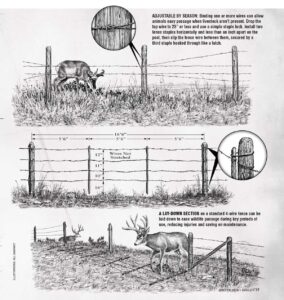

Yet fences are necessary in many situations. Luckily there are proven techniques to make both existing and new fences easier on wildlife. The goal is to create fences that are low enough to jump, high enough to crawl under, less likely to tangle legs and highly visible—yet still retain their function. There really isn’t a single fence design that will fit every situation, and landowners and land managers are ahead to tailor their fence design to specific needs and terrain. But the following ideas offer some solid benchmarks.

For deer and elk, the top of the fence should be no higher than 40 to 42 inches. A healthy adult animal can typically clear that height on level ground. On a steep hillside, however, the effective fence height from below is much higher. Best solutions in this situation are to drop the top wire or install a wildlife pass (more on this shortly).

Pronghorn, as well as young deer and elk, much prefer to crawl under fences. Traditionally, cowboys used the top of their boot, roughly 12 inches, as a convenient gauge for stringing the bottom wire, but that’s often much too low for animals to slip under. A recent study in Alberta by researchers with the Alberta Conservation Association found that pronghorn prefer a minimum of 18 inches of clearance under the bottom wire or rail—anything less can be tough for adult animals to slip under, and many pronghorn rip hair off their backs scrambling under low barbed wire strands. Some ranchers object that young calves can slip under an 18-inch wire too easily, but it’s a short window when they’re small enough to fit under, and temporary fencing can often bridge the gap. Also, wayward calves tend to quickly slip right back under again to get back to mom.

Elk, deer and other jumpers most often tangle their legs in the top two wires of a fence. Keeping wires tight, and spacing the top wires at least 12 inches apart—or installing a top rail made of wood or metal with the second wire 12 inches below—can reduce entanglements considerably. Installing smooth wire on the top and bottom also significantly reduces entanglements and tears. Making a fence more visible by using a rail or colored polywire on top helps animals better judge the height before a jump while also reducing collisions by low-flying birds—a real problem for sage grouse

and raptors.

Other designs can open up an entire fenceline to allow wildlife easier passage during migration when livestock aren’t present. For example, lay-down fence uses stays that are held to permanent posts by wire loops. A rider can easily slip the loops and lay the entire fence to ground. Or staple locks or small clips can be used to allow some or all strands to be lowered, making for easier passage. When cattle are present, high-tensile electric fence can contain them while letting elk blow through, their hollow hair insulating them from the shock. A moveable single-strand of electric fence can even be used for rotating pasture instead of a maze of pasture cross-fences. Of course it’s not always practical to turn every mile of fence into a wildlife-friendlier design, but it’s easy to install wildlife crossings and gates. Securing gates open when livestock aren’t present is an easy seasonal solution for wildlife. A simple wildlife pass at popular crossing points can be made in a single section of fence by installing three rails or taut smooth wire at 18 inches, 30 inches and 40 inches. Pulling the top two wires and bottom two wires together with wire clips or staple locks in a single fence section also creates a decent wildlife pass.

What about rail fences? A standard post and rail fence can be easier for elk to jump if it’s no higher than 42 inches and there’s room for young ones to slip under. But three-dimensional (i.e. triangular) buck-and-rail fences or, worse, buck-and-wire fence, can be a nightmare for elk to navigate. These can be modified by dropping one end of the top rail to the ground in some sections, leaving a small gap for wildlife, or building the fence with two rails only, bolted at 18 inches and 40 inches, and leaving off the internal rub rail in alternate sections so the fence is easier to crawl over.

Fences and the Foundation

RMEF has been helping remove and improve fences since 1987, when the Flagstaff Chapter got things rolling by pulling three-quarters of a mile of dilapidated and obsolete fence on the Coconino National Forest. Since then, the Elk Foundation has tackled more than 200 projects in 17 states, including fence removals, modifying fences to wildlife-friendlier designs, and construction of laydown fences, elk jumps and passes in livestock fences. These projects have been on public lands and private: national forest and BLM land, state wildlife management areas, private ranches adjacent to public land and RMEF conservation easements. RMEF has invested close to $1 million in fence modifications and removals over the years, often working through public and private partnerships to multiply the leverage of those funds. And that’s not counting the thousands of hours donated by RMEF volunteers.

Half of all these fence projects involved RMEF volunteers slipping on leather gloves, swinging fence pliers and rolling up wire to improve passage for wildlife. In just one example, on the Roosevelt-Arapaho National Forest this past July, 29 RMEF volunteers teamed up with Forest Service employees and a Colorado Parks and Wildlife biologist to tear out another two miles of derelict, collapsed fence in an area heavily used by elk, moose and mule deer. This was the ninth year that RMEF volunteers have gathered in the Troublesome Basin—home to some 4,000 elk. So far they have removed more than 15 miles of treacherous fencing.

The group braved a steady rain and sloshed through beaver ponds and soggy meadows to pull barbed wire and steel posts, much of them buried in tall grass and marsh. “Not a single complaint was audible,” reported RMEF volunteer Jerry Ellis. “A couple of lanky teenagers may have muttered something like, ‘We’re already wet, we don’t need no stinking waders,’ as they plunged into the beaver pond to retrieve fence posts.”

Ellis said it’s obvious what a barrier and entanglement hazard this fence has been for wildlife here, but they watched with pride as a cow moose with twin calves and a doe also with twins crossed freely where not long before there was a fence.

“That brought a satisfied smile to us all.”

All told, over the years RMEF funding and volunteers have helped remove at least 284 miles of fence and modify another 254 miles—or 538 miles in total at a bare minimum (not all volunteer projects get reported to RMEF headquarters to be tallied). Figuring four strands of wire on most fences, that’s enough barbed-wire to stretch east to west all the way across Montana—and back. The Elk Foundation’s core mission is better habitat for elk and other wildlife, and fence removals and improvements give us big bang for our bucks and our volunteer time.

We may never know how many four-legged lives these projects have saved over the years, but wherever an abandoned fence is gone or an existing fence is made easier to hurdle, elk and their kind can flow more freely across landscapes, tracing the paths they have known for millennia.

Christine Paige is a wildlife biologist and writer who wanders the wilds from her home in Driggs, Idaho. She has authored two handbooks on wildlife-friendlier fences.

Hold a Fence Party

RMEF chapters far and wide have gotten involved in fence projects—a great way for elk-lovers of all stripes to invest in wildlife stewardship and build good relations with neighbors. Many projects involve folks of all ages and abilities. There are opportunities to remove obsolete fences where they’re no longer needed for livestock, such as retired grazing allotments on public land and conservation easements on private land. It doesn’t take much more than a volunteer crew, permission from a landowner or manager, a bunch of leather work gloves and fence pliers, and a wire-winder to bale the barbed wire. (Just be sure everyone’s tetanus shot is up to date!) Enjoy a day in the field and a picnic lunch, get a couple of pickups to haul the scrap wire to recycling (which can be a money-maker for a chapter, too), and you’ve opened up another chunk of ground for the critters.

Fence modifications, elk jumps and wildlife passes take more planning, investment in materials, and know-how, but these absolutely can be done through partnerships. Some projects might even require a bit of heavy equipment operation, but many simply require switching out barbed wire for smooth wire and changing the wire heights. Keep in mind that while it would be ideal for every mile of fence to be altered to wildlife-friendlier standards, it’s possible to target the trouble spots and make easier passage where most animals cross.

Want to get your RMEF chapter involved? Start by talking to local resource managers with the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management, Natural Resources Conservation Service field offices and land trusts—including RMEF. These folks often have a list of fence projects where a crew of volunteers can make a huge difference.